From prototypes to classes

The term 'object-oriented programming' (OOP) is the source of a great deal of confusion. One of the most common definitions centers around classes, central to typical OOP languages like Java, C++, Ruby, and Smalltalk. Enormous amounts of software has been built in these languages, and to a lot of programmers there's nothing wrong with the following definition:

Yet, there exist languages that are object-oriented but lack these concepts. In them, objects inherit directly from other objects through delegating to prototypes. The best known example of this is Javascript, though the idea was first extensively explored in the influential Self system, and initially tested in production in Newtonscript. Although these languages lack classes, a wide variety of class systems were successfully simulated with prototypes, indicating we should be looking deeper for the meaning of OOP.

Javascript

In Javascript, constructor functions serve to build objects and organize methods. Object behavior can be specialized without having to define a new class, instead preempting prototype delegation by simply setting a property. A tortured example:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype.greeting = function() {

return `Hi ${this.name}`;

}

let test = new Person('Tester');

console.log(test.greeting()); // Hi Tester

test.greeting = function() {

return `What's up ${this.name}`;

}

console.log(test.greeting()); // What's up Tester

In this way, the behavior of the test object was changed by directly changing the object itself, because the greeting method being called is just a property. Delegation operates by querying for missing properties in the prototype, going up the chain until that prototype doesn't have a next one. Functions are first-class objects bound to the receiver but otherwise the semantics are the same.

In Javascript, it is easy (but dangerous) to extend the base types.

String.prototype.end = function() {

return this[this.length - 1];

}

console.log('hmm?'.end()) // ?

This style of programming wasn't loved by programmers, especially those coming from a C++ or Java class-based background. Closures shined among serious programmers like Douglas Crockford, who explored how classes could be accomplished in Javascript in 2002 (but later repented for suggesting foisting classes on JS). There were even JQuery-era frameworks that added classes, like Prototype (used in Ruby on Rails) and MooTools (used by Bret Victor).

The first real attempt to add classes to the language was in the failed Ecmascript 4 standard, also adding interfaces, a nominal and structural type system, multimethods, namespacing, packages, generics, and perhaps most radical of all, integers. There was a great deal of debate about, as Self's David Ungar put it lightly, "the richness of the additions to the language". Brendan Eich tried to dissuade programmers convinced that Javascript was becoming its namesake in a @media Ajax Keynote:

I hold no brief for Java. JS does not need to look like Java. Classes in JS2 are an integrity device, already latent in the built-in objects of JS1, the DOM, and other browser objects. But I do not believe that most Java U. programmers will ever grok functional JS, and I cite GWT uptake as supporting evidence. This does not mean JS2 panders to Java. It does mean JS2 uses conventional syntax for those magic, built-in “classes” mentioned in the ES1-3 and DOM specs.

In other words, and whatever you call them, something like classes are necessary for integrity properties vital to security in JS2, required for bootstrapping the standard built-in objects, and appropriate to a large cohort of programmers. These independent facts combine to support classes as proposed in JS2.

For a bevy of reasons, the ES4 proposal was ultimately abandoned for ES3.1, with many of the ideas from ES4 carried on in ECMAScript Harmony. Eventually, they become the nice features that have made Javascript one of the most popular programming languages today (and ever). The classes, however, were reeled in, as the Harmony proposal explains:

Other goals and ideas from ES4 are being rephrased to keep consensus in the committee; these include a notion of classes based on existing ES3 concepts combined with proposed ES3.1 extensions.

So, no more multimethods, this is still required for scoping, and no nominal or structural type system (though TypeScript would bring that later). ES6 classes can be helpful but they aren't very flexible, especially compared to those of more metaprogrammable systems like Smalltalk or CLOS. The triumph of React hooks over classes in an area where they typically excel is a clear indictment of their shortcomings (though not everybody is happy with that). Their lack of flexibility means it's an easy mistake to use them as abstract data types, at which point they only serve to make the functional parts of the language more awkward.

Though saddled with a gimped class system, the prototypical object system and first-class functions that make Javascript so dynamic are still there and ready to be (ab)used. Countless examples attest to its attractiveness as a target for compilation of a higher level language, which Alan Kay recently mused about at the recent event celebrating the 50th anniversary of Smalltalk:

...Javascript is a little bit of a hodgepodge, but underneath, it has both a model that I think of as being a bit more like Lisp, and a really solid set of foundations, including a really great garbage collector, fabulous optimization. So it's a little bit of a scattershot of a language, but as something to treat, for example, as the machine code of the next machine you want to turn into something wonderful, Javascript is actually pretty good for the reasons that Lisp is pretty good. You've got this dynamic language, something where things run pretty fast, you've got WebAssembly if you want to make things run even faster. It, in my opinion, is probably the simplest place for both doing experiments and doing things that you want to deploy today.

WASM might eventually be the main target for languages on the Web, but for now it lacks a lot compared to Javascript, like GC and JIT support, and isn't even that much faster in many cases. Some aspects, like W^X, make implementing a dynamic, incremental language much more difficult. Meanwhile, JS engines like V8 and WebKitCore are constantly being optimized and run everywhere.

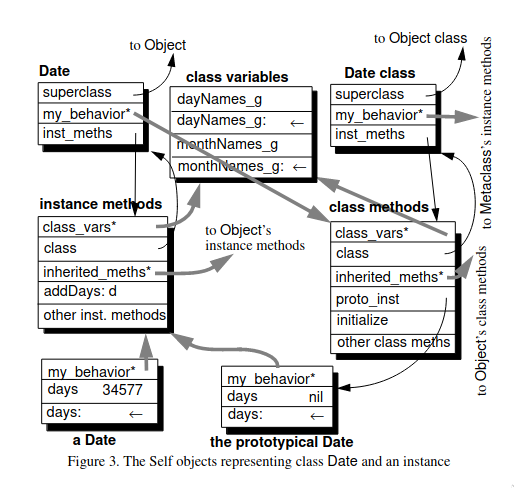

Self

Before Javascript, there was Self. Self was inspired by Smalltalk, especially in its approach to message passing:

Self features message passing as the fundamental operation, providing access to stored state solely via messages. There are no variables, merely slots containing objects that return themselves. Since Self objects access state solely by sending messages, message passing is more fundamental to Self than to languages with variables.

This mirrors Kay's later email on messaging:

The big idea is "messaging" -- that is what the kernal of Smalltalk/Squeak is all about (and it's something that was never quite completed in our Xerox PARC phase). The Japanese have a small word -- ma -- for "that which is in between" -- perhaps the nearest English equivalent is "interstitial". The key in making great and growable systems is much more to design how its modules communicate rather than what their internal properties and behaviors should be. Think of the internet -- to live, it (a) has to allow many different kinds of ideas and realizations that are beyond any single standard and (b) to allow varying degrees of safe interoperability between these ideas.

The Self VM pioneered techniques in adaptive optimization for dynamic languages, notably Urs Hölzle's runtime type feedback. Many of its optimizations would later be put to use in V8 by fellow Self VM wizard Lars Bak.

Later in the project, it was shown that both Smalltalk and Java could be implemented in Self, a feat which also happened to produce a much faster Smalltalk implementation.

Strongtalk was a type-checked version of Smalltalk built on the Self VM. Originally created when Sun shuttered the Self team, it was ultimately bought back by Sun three years later and became the HotSpot JVM. This fate seems to have disappointed the Smalltalk community, at least as I gather from an aside by Dan Ingalls at the aforementioned Smalltalk event. It had a very smart type system that supported the flexibility of Smalltalk, but the Smalltalk ecosystem had collapsed with the rise of Java and the Web, and by the time Strongtalk was open-sourced, its moment had passed.

Newtonscript

There's one more prototypical language worth mentioning - Newtonscript, developed for the ahead-of-its-time Apple Newton. Prototypes offered a way to save on precious memory (the original launched with 640K RAM) and were fast enough for the modest processor. For simple GUI scripting, the object system included a parent slot used for view inheritance as well as a normal prototype slot. The parent slot was later found useful for an informal class system extensively used on the Newton.

So what is OOP?

What's interesting about these examples is that none were deliberately designed to be turned into a class system, yet they all accomodated one. Prototypes appear to be a more primitive inheritance mechanism than classes, which are moreso a very useful design pattern - it's just hard to see as they're so ingrained within their languages. There are yet more kinds of object system. Actors, the basis of Erlang and Scheme.

When they were introduced, classes were necessary for implementation on limited hardware and helpful for organizing behavior, so they remained key features in later languages, just as how those languages retained structured conditionals and loops while Smalltalk and Lisp showed that they could be integrated into the base language quite easily. Treated uncarefully, these mixed metaphors quickly become design flaws that give experienced programmers a bad taste for OOP.

Prototypes imply that OOP shouldn't be defined in terms of classes. Instead, as Alan Kay said, the "whole point of OOP is not to have to worry about what is inside an object". Encapsulation is the ultimate goal and messaging is the means. This lets programmers drop into the shoes of objects and reason about how they work just like children learning LOGO can reason about the turtle as it moves. A skill like programming is much more graspable if the user can bring in experiences from other domains, as metaphors and points of view. The success of object-oriented programming is not some conspiracy - it acknowledges the human at the other end and helps them build a world of meaning in software.